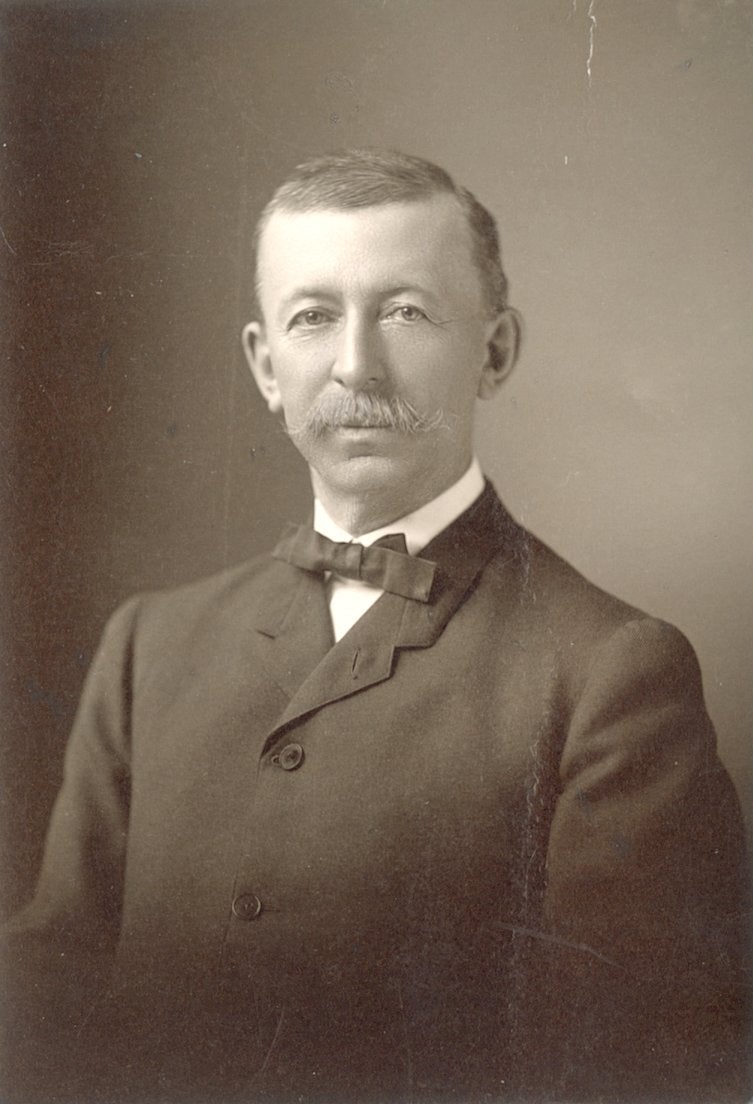

Edgar Fahs Smith, the thirteenth provost of the University of Pennsylvania, was born in York, Pennsylvania, in 1854. Smith attended the York Country Academy before joining the junior class at the Pennsylvania College at Gettysburg (later Gettysburg College) in the fall of 1872. Smith graduated from the Pennsylvania College at Gettysburg in 1874 and soon thereafter traveled to Germany where he would further study chemistry, earning his Ph.D. in 1876.

Upon his return to the United States, Smith was named an associate professor of analytical chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. Although he left Penn in 1881 to become the Asa Packer Professor of Chemistry at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Penn was never far from his heart. Smith returned to Penn in 1888 after also severing as a professor of chemistry at Wittenberg College in Springfield, Ohio.

Upon his return to Penn, Smith became a full professor of analytical chemistry. Three years later his title was changed to professor of chemistry and in 1893 he was named director of the Chemistry Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1899, Smith was named vice provost of the University. Eight years later he was named the Blanchard Professor of Chemistry, a position he held until his retirement. In 1910, Smith was named provost of the University of Pennsylvania, a position he held until 1920, when he retired from most of his commitments at Penn. Smith also served Penn as the manager of the Wistar Institute from 1915 until 1922 and as an emeritus professor of chemistry from 1920 until his death in 1928.

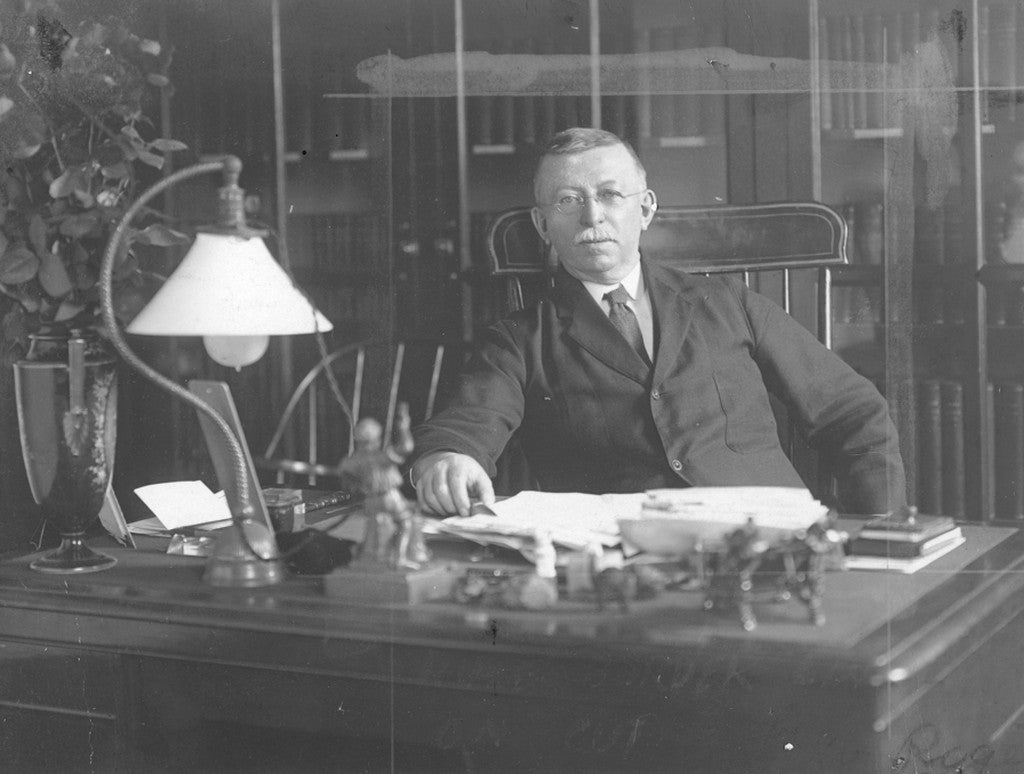

Smith was a top-notch administrator who instituted numerous new policies that changed Penn for the better. During his tenure at Penn, Smith ended the Bachelor of Science program intended for those students who did not take Greek while at Penn. In place of a Bachelor of Science degree, these students were to receive the same Bachelor of Arts degree that all graduates of the College at Penn received. Smith mounted a successful campaign to raise the course requirements for graduation from the College at the same time he split the “old College” into four divisions, the College, the Towne Scientific School, the Wharton School of Finance, and the School of Education. Smith also split the Department of Engineering into the Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Department of Electrical Engineering.

Smith’s changes at Penn were not merely structural; during his tenure as provost, enrollment doubled, the number of instructors in the University increased from 400 to 700, and many millions of dollars were donated to Penn allowing for a tremendous increase in professor’s salaries and construction on campus. Perhaps Smith’s biggest influence on the future of Penn, however, was his stance on women and education. While he was a professor of chemistry, Smith had a number of women students who worked along side his male students in his lab. His most influential stance on women’s education occurred while he was provost, when he had women admitted to the Dental the Medical Schools.

Smith’s academic excellence and his skill as a chemist were recognized many times by colleges and universities the world over. He received three honorary degrees from Penn during his lifetime; the degrees of Doctor of Science in 1899, Doctor of Laws in 1906, and Medical Doctor in 1920. Aside from the three honorary degrees Smith received from Penn, he received, at best count, sixteen other honorary degrees from such prestigious and geographical wide-ranging institutions as Princeton University, the University of Dublin, Ireland, and Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada.

Smith was also well recognized outside of the great many honorary degrees he received in his lifetime. He served as the president of the American Philosophical Society from 1902 until 1906 and as the president of the American Chemical Society in 1898, 1921, and 1922. He also was awarded the very prestigious Priestly Medal from the American Chemical Society in 1926. He received the Chandler Medal from Columbia University and the Eliot Cresson Medal from Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute as well. The French government honored Smith by naming him a member of the French Legion of Honor in recognition of his work in chemistry.

Throughout his life, Smith collected memorabilia from chemists across the ages and often wrote about the chemists whose memorabilia he collected. Upon his death, his wife donated the collection of memorabilia to the University of Pennsylvania where it was immediately put on display and named “The Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection in Historical Chemistry.” For a number of years following his death the University honored Smith through the “Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Lectures” on chemistry. Smith is now memorialized on campus by a statue which rests across from the Fisher Fine Arts Library as well as the walk leading up to the statue, known as Smith Walk.