By early 1965, the UCSC was eager to find a building of its own to occupy (it had been renting space in the Widener Building on Chestnut and Juniper Streets). Through a City Council Ordinance on 12 January 1965, the UCSC acquired the building at 3401 Market Street, which had served as the headquarters of the printing firm Stephen Greene Company. Within weeks, the UCSC (whose membership had by now increased to eleven institutions) received its first research contract, for a two-year, $150,000 study of viruses underwritten by the Johnson & Johnson Company. Throughout the rest of 1965, the UCSC undertook a large renovation program for 3401 Market (“Building Number One”) to prepare it for the needs of a center devoted to scientific research. At the same time, the Center actively recruited potential customers for its research facilities, sending out a promotional pamphlet entitled “Come to Where the Knowledge Is.” By the start of 1966, Building Number One housed the Reentry Systems Department of General Electric Co., the Institute for the Advancement of Medical Communications, and the Architectural Research Institute, in addition to the UCSC’s own offices. It is unclear whether the UCSC completed the Johnson & Johnson virus study at Building Number One, if at all.

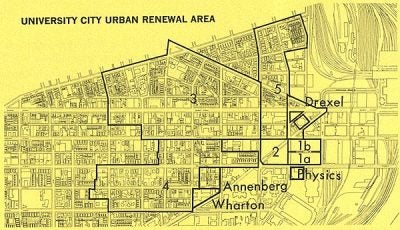

At the same time that its Building Number One was being renovated, the approval process for the Science Center’s redevelopment in Unit 3 was moving ahead. The UCSC submitted development and marketing proposals to the RDA in July 1965, and City Council held a public hearing on 14 October 1965 to discuss these plans. Surprisingly the author has not found evidence of any major community outcry at this meeting. On 24 November 1965, Mayor Tate signed into law an ordinance that had been passed by City Council earlier that month to authorize the RDA to execute its redevelopment contract with the UCSC. This ordinance described the precise boundaries of the UCSC redevelopment area within Unit 3: beginning at the northwest corner of 34th and Ludlow Streets, west on Ludlow to 40th Street, north on 40th to Market Street, east on Market to 38th Street, north on 38th to Filbert Street, east on Filbert to 36th Street, north on Filbert to Warren Street, southeast on Warren back to Filbert Street, east on Filbert to 34th Street, south on 34th to Ludlow Street and the place of beginning.

Despite its apparent lack of protestation during the City Council hearing, the community had by no means become idle. In November 1965, the same month that City Council approved the UCSC plans, the Tabernacle Church in West Philadelphia created a Volunteer Community Resources Council (VCRC) to provide service in community organization, family planning, and counseling. According to Lacey Harwell, the Pastor at Tabernacle, the purpose of the VCRC was to help people in the community to help themselves: “We avoid the role of advocate for anybody.” Later in the decade, the VCRC would play a role in the development of housing units in Unit 3 (see below).

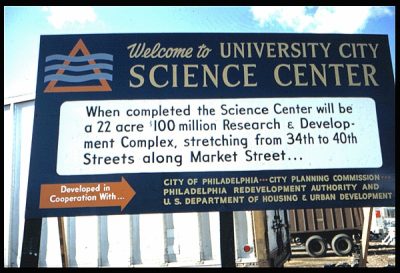

At the outset of 1966, it appeared as if the dream of the University City Science Center was quickly becoming a reality. A Philadelphia Inquirer editorial from late 1965 had stated of the Science Center, “No project attempted since 1950 has been more important to maintaining the vitality of the city and providing a solid foundation for continued and rapid development…. All Philadelphians can watch this project with pride.” Then on 30 April 1966, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced that it had approved a grant of almost $13 million to the RDA for redevelopment proceedings in Unit 3. After hearing the news, Leo Molinaro, the executive vice president of the West Philadelphia Corporation, stated that “actual condemnation of existing buildings can start within six months. We were afraid that this would have had to drag on until next year.” This last statement turned out to be ironica lly prophetic, for several factors combined to delay the redevelopment process for the UCSC into 1967.

Even before City Council had approved the RDA’s contract with the UCSC, there were reports that speculators had been purchasing real estate in redevelopment areas for several years with the hope of selling it to the RDA at a profit. Because it would likely command the most money from the RDA, the proposed Science Center land was regarded as “the prime area for speculation.” In an attempt to stem the profiteering, the RDA began to research the history of the land scheduled for redevelopment on a parcel-by-parcel basis, seeking out ownership patterns that would hint at speculation. Even without the speculation problem, though, the redevelopment process would have been delayed in 1966.

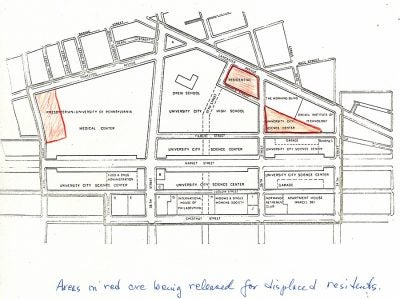

In late July 1966, almost three months after HUD approved the federal grant for Unit 3, seven “civil-rights advocates” warned the Philadelphia-area regional director for the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that local residents might start to riot if the RDA began condemning land in Unit 3. Robert C. Weaver, the Secretary of HUD, had adopted a policy of reviewing all redevelopment projects involving threats of racial tension before releasing any federal money, so the RDA did not immediately receive the grant that HUD had approved. Most of the agitation and tumult in Unit 3 was focused in area of the planned University City High School, but the Science Center project was delayed as well when HUD did not disburse its grant to the RDA. The potentially violent situation was finally defused after a delay of several months when the RDA promised to return 7.6 acres for public housing “in scattered sites” throughout Unit 3. One of the returned pieces of land was the triangular plot bounded by 36th, Warren, and Filbert Streets that had originally been allotted to the Science Center. Finally on 13 December 1966, HUD disbursed a capital grant of nearly $12 million, slightly smaller than the grant approved in April, to the RDA for redevelopment proceedings in Unit 3. Conforming to the regulations established by the Housing Act of 1949 and its successors, this $12 million grant covered two-thirds of the RDA’s estimated $18 million net cost of preparing Unit 3 for redevelopment. The payment of the federal grant marked the end of the planning stage of the redevelopment process.

Many residents of University City were still prepared to fight the destruction of their homes, however, and for the first time, student groups at Penn really seemed to take an interest in the situation just north of the University campus. Lawrence Beck and Stephen Kerstetter, two graduate students at the University, spent parts of their fall semester in 1966 visiting the “slums” of Unit 3 and interviewing residents. They published their findings in a five-part series entitled “The Quiet War in West Philadelphia” that ran in the Daily Pennsylvanian, the University’s student newspaper, from 23 January to 27 January 1967. “The Quiet War,” which was sympathetic to the displaced residents, stood out not only because the Daily Pennsylvanian rarely featured a series but also because its five articles were among the first in that paper to discuss the redevelopment proceedings in Unit 3. Felton Newman, one of the area residents whom Beck and Kerstetter interviewed, claimed that “the West Philadelphia Corporation is a front for the University of Pennsylvania” and that Penn was “fostering segregation by moving all Negroes out of the area.” The graduate students also found that other residents seconded the idea that “urban renewal means Negro removal.”

Some data helps to support these residents’ allegations. According to data from the 1960 federal census, non-whites lived in 333 of the 429 occupied units (77.6%) in what was to become the UCSC redevelopment area. Ten years later, after the land in Unit 3 had been cleared, the census recorded that only fifteen dwelling units remained in the Science Center area. Redevelopment moved nearly all residents-most of whom happened to be black in this case-out of the area. One could also make a case that Penn was in control of the UCSC. As of April 1967, Penn owned 2000 shares in the Science Center whereas the other eighteen member institutions held 100 shares each. It does not appear, however, that Penn dominated the UCSC’s Board of Directors or even its Executive Committee during this period, and its President Gaylord P. Harnwell maintained that the University’s policy was only to provide financial assistance to the Science Center in its formative stages, especially by guaranteeing its initial expenditures.

In early 1967, the RDA, undoubtedly eager to implement the redevelopment process, initiated eminent domain proceedings in Unit 3. Eminent domain, also known as condemnation, is the legal process by which the federal or local government reserves the right to take over private property- with fair compensation-for the good of the people. For example, eminent domain proceedings take place every time a new road (or stadium) is built. In the case of Unit 3, the RDA determined its fair compensations by paying all moving costs and consulting with at least two assessors for land and structural values and, for businesses, machinery and equipment damage. The RDA would likely use most of the $12-million federal grant to pay for these real estate and relocation fees; the old Urban Renewal Administration had reported that, through 31 December 1962, 66.8% of all federal money for urban renewal programs had been used to cover real estate purchases alone. As of March 1967, 43% of property owners in Unit 3 had accepted the RDA’s price, and the RDA began to demolish vacant properties in the UCSC area that August.

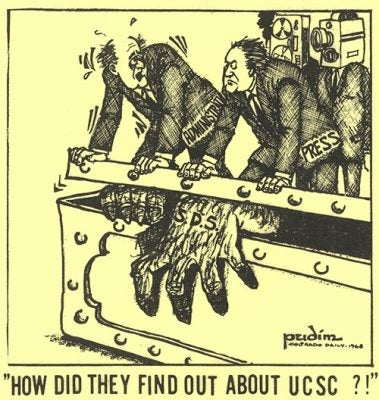

Controversy continued to accompany the development of the Science Center in 1967, but, surprisingly in the year in which most Unit 3 properties were razed, the major conflict was not directly related to displacement. Almost since its inception, the UCSC had accepted (and perhaps even relied on) lucrative government-sponsored research projects. As of late July 1967, seven of the nine “research and development projects” that the UCSC had under contract were for the federal government. Four months earlier, on 21 March 1967, the Executive Committee of the UCSC had reaffirmed that “one of the functions of the University City Science Center is to undertake projects which for security or proprietary reasons, or because of problem-oriented objectives, are not compatible with the research policies of the individual educational and life science institutions who are members of the Center.” In this era of “flower-power” and widespread protests against the Vietnam War, rumors that the UCSC (of which Penn still owned a majority of shares) might accept government-sponsored research into chemical and biological warfare enraged many students at the University. Jean Paul Mather, the executive Vice President of the UCSC, did nothing to quell these rumors and in fact voiced his support for war-related research.

Referring to a statement made in Congress in the spring of 1967 that the Soviet Union outclassed the United States in chemical and biological weaponry, Mather remarked, “I don’t think we should be ignorant to what our enemies are doing.” In late April 1967, the students took their grievances directly to President Harnwell in the most confrontational manner. In an extraordinary understatement, the minutes of the University’s Trustees reported that “a small group of students (perhaps about 150) staged a sit-in in the President’s Office” to protest secret war-related research at both the University and the UCSC [italics added by author]. Following President Harnwell’s recommendation in response to the student protestors, the Trustees agreed on 4 May 1967 to terminate two controversial classified research contracts at the University (Projects Spice Rack and Summit). On the other hand, the UCSC’s Mather reacted quite differently to the protestors. “Those beatniks on the street can go climb a tree as far as I’m concerned,” he declared. “If pickets show up, I’m going to have them arrested as trespassers.”

The year 1968 marked a great milestone for the Science Center, as construction began in June for the first entirely new building in its complex, at 3508 Market Street. The Science Center hoped to complete the new building, which was called “Building Number Two,” at a cost of $1.5 million by the end of 1969. Meanwhile, property clearance continued in Unit 3. By August 1968, one year after demolition began, there were only a few buildings left standing in the Science Center area. These included: on the north side of Market Street, Crown Laundry (between 34th and 36th Streets), and on the south side of Market, the hardware company C.L. Presser (between 34th and 36th Streets) and “Bernie’s bar” (between 36th and 37th Streets).

Also in 1968, the Volunteer Committee Resources Council (VCRC) undertook a survey of 400 people who had been displaced by redevelopment in University City Unit 3. In general, the survey suggested that the former residents were now living in better housing but were also paying higher rents; that about half of the displaced persons considered the moving expenses they had received to be “inadequate”; and that most (55%) former renters and some (15%) former homeowners desired to return to their former neighborhood.

Meanwhile, student protest at Penn reached new heights. A special meeting of selected University Trustees took place on 8 July 1968 to address “certain sensitive questions to which continuing attention should be directed.” The Trustees at the meeting further stated that “the most immediate problem of some concern is that of the University City Science Center, in which the University owns 51% of the stock and where there is a Defense Department contract where the results are deemed classified.”

The Trustees’ concern over this matter was prescient, for in November 1968, Penn students affiliated with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a radical protest group that flourished in the 1960s at college campuses all across the country, created a list of seven “demands” regarding the UCSC and its relationship with the University. In general, the demands called for the end of war-related research at the UCSC, student and community involvement in decisions related to Penn’s expansion, and University and UCSC commitment to providing public housing in University City. One student involved with SDS, Mark Bauer, further demanded that the University’s entire Board of Trustees resign.

It is open to interpretation whether the student protestors at Penn were truly concerned about the displacement of University City residents. The author’s view is that most students would not have protested the displacement if the Vietnam War had not been going on at the same time. Many students in the 1960s probably felt compelled to participate in protests by a kind of counter-cultural peer pressure. Because both of them were seen as causes of the “establishment,” displacement in University City and the war in Vietnam both served as appealing targets of student protest. There were students like Lawrence Beck and Stephen Kerstette r who genuinely seemed to care about the welfare of the University City community, but they were relatively few in number compared with those whose motivations for protesting displacement and the Science Center were primarily political.

The SDS persisted in an effort to get the University administration to respond to its list of demands, and on 6 December 1968, several SDS members were able to meet with President Harnwell. Over the students’ winter holiday, Harnwell worked with his advisors to formulate a written response to the SDS demands. On 16 January 1969, after the students had returned to the University, Harnwell sent his official statement to Jules Benjamin of the SDS, with additional copies going to the Daily Pennsylvanian (for students), the Almanac (for faculty), and the Pennsylvania Gazette (for alumni), as well as to the Information Center on campus.

The SDS, however, was anything but satisfied by Harnwell’s response; “University Administration, the Artful Dodgers,” read one of the group’s subsequent posters. Then on 18 February 1969, some Penn students affiliated with SDS joined with students from “other educational institutions holding stock in the Science Center” to occupy College Hall spontaneously in protest over both the possible existence of classified military-related research at the UCSC and the displacement of former University City residents by the UCSC. After days of negotiations between students, faculty, and the administration, the sit-in was resolved on 23 February when the Executive Board of the Trustees approved the demonstrators’ proposal to establish a special commission to insure that University development would not conflict with community development. The Trustees’ statement read, in part:

The University has accepted the principle of community involvement by means of a quadripartite commission composed of community leaders, faculty, students and administration as a means of jointly advancing and coordinating community and University development and as a mechanism for securing community consent to development plans.

The Trustees declare a policy of accountability and responsibility that accepts the concerns and aspirations of the surrounding communities as its own concerns and aspirations and that to insure community of purpose in joint initiation, planning and execution of programs and effective mobilization of University talents and facilities, the quadripartite commision [sic] shall be the instrument through which these activities, at least initially, shall be carried out and that commission shall proceed to its work with the utmost urgency as set forth, in part, below.

The Trustees resolve that in order to proceed with immediate effectuation of this policy, that

- The quadripartite commission shall, at least initially, be composed of five community members designated by Renewal Housing, Inc., five University of Pennsylvania students designated by the community of demonstrators, five faculty designated by the University of Pennsylvania Faculty Senate, all but one of whom must be resident in West Philadelphia, and five Trustees or their representatives, and

- the quadripartite commission shall be empowered to review and approve all existing plans involving future land acquisition or development of currently owned land contiguous to existing residential neighborhoods, and shall be informed of the initiation of all such future plans and studies, and

- that the quadripartite commission shall operate on the principle that in all future University expansion which involves demolition of existing housing units, the University undertakes to guarantee the provision of an equivalent number of housing units at equitable prices and rentals, and

- that, in keeping with the principle of accountability and responsibility of the University to the surrounding community the members of the Board of Trustees individually and collectively agree to concert their efforts through the corporations, business, institutions and agencies to which they have access, to develop the funds and funding sources needed for community renewal programs with the goal of establishing a community development fund with resources of $10,000,000.

For a while, it seemed that the quadripartite commission (whose formal name was the Commission on University-Community Development) would actually satisfy all the involved parties. Yet scarcely one month went by before protest renewed, this time from the community. After a meeting on 30 March to discuss community representation on the commission, members of the Philadelphia Community Union (PCU) proposed that two-thirds of the positions on the commission be held by representatives of the community. The next night, the Reverend Charles Riley, pastor of the Church of the Good Life in Mantua and a member of the PCU, picketed a meeting of the quadripartite commission in protest. He claimed that the commission was “neither representative [of] nor responsive” to the community and proposed that community representatives on the commission be elected, not appointed, and that the commission’s meetings be open to the public. In response to these voices of disapproval, L. Lorenzo Graham, the president of Renewal Housing, Inc. (RHI), agreed at the commission’s 15 April meeting to reduce the group’s seats on the commission from five to three, effective immediately, with the possibility of more cutbacks in the future.

The same week that the RHI reduced its number of seats on the quadripartite commission, another objective of the February sit-in (and earlier student protests) was resolved when the board of directors of the UCSC agreed to refuse all research whose purpose was the “destruction or incapacitation of human life.” Then in June 1969, Dr. Jean Paul Mather, whose incendiary comments regarding classified research at the Science Center had stirred up much controversy two years earlier, resigned as president of the UCSC. After these two significant changes, the Science Center’s image gradually began to improve among students and the community. Meanwhile, work on Building Number Two was proceeding nicely, and in June 1969, the Science Center was ready to begin construction for Building Number Three, at 3500 Market Street. This new building was to house the Monell Chemical Senses Center, an interdisciplinary research center for studying the senses of taste and smell which the University of Pennsylvania had established the previous year with a $1 million grant from the Ambrose Monell Foundation of New York.

As 1969 progressed, conflict continued to delay the work of the quadripartite commission. In September, the student and community representatives declared that they would not consider the commission a success in any way until a community development fund existed as agreed upon that February. John Eckman, a representative of the University’s Trustees, countered that the University had a deficit as it was and that the Trustees “did not and could not commit [themselves] to an endowment fund,” as the students and community were seeking. By the end of the month, a so-called “charrette”-an architectural term for the final intensive effort to complete a project within a deadline-was underway to create a new redevelopment plan for Unit 3, with the goal of integrating the community’s need for low-income housing with the redevelopers’ plans for the land. In late October, the quadripartite commission approved the revised redevelopment plan, which called for the creation of 400 additional units of low-income housing. Community groups began to speak out against the plan almost immediately. Objecting to the estimated price of the new housing, one black woman asserted that “a $16,000 house is just another way of saying `black man get out.'” Other groups like the PCU and the Concerned Community Council expressed anger that the community was represented on the commission by Herman Wrice, president of the Young Great Society, and Andy Jenkins, president of the Mantua Community, neither of whom (according to student representative Cathy Barlow) attended commission meetings with any regularity or even “[wanted] to work with the community.”

The community groups were not alone in their dissatisfaction with the quadripartite commission’s redevelopment plan. One of the five parcels of land the commission intended to use for public housing was the plot owned by the UCSC on the south side of Market Street between 34th and 36th Streets. The commission believed that this land was not essential to the Science Center’s mission and so initiated discussions with the UCSC in January 1970 over its return. At first, Science Center officials were averse to handing over any land, declaring that doing so would disrupt the “continuity” of the center. But on 17 February 1970, the eve of the first anniversary of the sit-in at College Hall, the UCSC’s executive committee resolved to allow the quadripartite commission to oversee the development of low-income housing on a different parcel of its land, between 39th and 40th Streets on the south side of Market Street. Despite this good news, internal dissension continued to bring the quadripartite commission to near collapse. The main point of contention continued to be the community development fund that the University’s Trustees had promised to provide, in whatever form, back in February 1969. With this issue still unresolved as the second anniversary of the College Hall sit-in approached, interest in the commission faded. By a unanimous vote on 8 February 1971, the quadripartite commission quietly agreed to disband.