Summary Information

- Prepared by

- J.M. Duffin

- Preparation date

- 1999

- Date [bulk]

- Bulk, 1938-1971

- Date [inclusive]

- 1863-1973

- Extent

- 211.0 Items

PROVENANCE

The archival records that form this microfilm collection are taken from the collections of three institutions: the Charles Babbage Institute of Computer History (CBI), a research center at the Walter Library of the University of Minnesota (http://www.cbi.umn.edu/index.html); the Hagley Museum and Library (HML), an independent research library near Wilmington, Delaware, whose collections document the history of American business and technology, particularly in the Mid Atlantic region (http://www.hagley.org/library/) and the University Archives and Records Center of the University of Pennsylvania (UARC), an institutional repository whose collections primarily document the history of the University of Pennsylvania (http://www.archives.upenn.edu). Each of these three holds significant, but incomplete collections of the trial exhibit records submitted into evidence by the plaintiff and defendants in Federal Case 4-67-Civ. 138, Honeywell Inc. vs. Sperry Rand Corporation and Illinois Scientific Instruments, Inc. This case was filed and heard in the U.S. District Court, Fourth Division of Minnesota at Minneapolis between 1967 and 1973.

Historians of science and technology generally regard Honeywell vs. Sperry Rand as the definitive forum for the debate over and settlement of all patent and other intellectual property claims to the invention of the computer. The plaintiff and defendants introduced a comprehensive set of primary sources documenting the history of the development of the first digital computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) and the early years of the computer industry. In 1984 Honeywell, Inc. donated its plaintiff’s trial records to CBI. A year earlier Sperry-Rand had placed its defendants’ records on deposit at HML. In 1989 the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Pennsylvania transferred its copies of the trial records to UARC. By combining the exhibit records of both plaintiff and defendants in a temporary, best-copy, “master” collection, the three collaborating institutions effectively recreated the extraordinary resource which had only fleetingly existed at the trial itself.

The target sheet for each trial exhibit and the master collection inventory which follow below both state the institutional collection to which a given exhibit belongs. Subsequent to microfilming and the application of appropriate quality control reviews, the project archivist disassembled the master collection and returned its constituent parts to the contributing institutions.

The exhibits used from the Charles Babbage Institute were taken from the “Honeywell, Inc.: Honeywell vs. Sperry Rand Records, 1864 – 1973” collection (Accession number 985-007; Collection number CBI 1). Honeywell, Inc. donated this collection to CBI in 1984. The collection contains nine records series – indexes to the collection, pretrial deposition testimony, deposition exhibits, deposition photographic exhibits, the plaintiff’s briefs, trial testimony, the plaintiff’s trial exhibits, final judgment, and miscellaneous – assembled by Honeywell, Inc. over the long course of the litigation. The largest of these records series, by far, is the plaintiff’s trial exhibit series. This series consists of the plaintiff’s first 6,000 trial exhibits and extends to 70% of the collection. Almost all these exhibits are the actual documents submitted to the court, as revealed by the color sticker affixed to the documented and annotated with the exhibit number. The ENIAC Trial Records microfilming project utilized nearly all the plaintiff’s exhibits in the CBI collection. The CBI collection does not contain any defendants’ trial exhibits.

The Hagley Museum and Library’s contribution to the master collection was a record series within its “Sperry-Univac Records, 1935 – 1973” collection (Accession number 1825; HML does not further organize its archival collections in accordance with a collection number or classification system). This collection is composed of four records groups, one of which, “Records of the Sperry-Honeywell Lawsuit, 1935 – 1973,” contains two records series, the “Original File, 1941 – 1955” and the “Chronological File, 1935 – 1973.” The Chronological File consists of photocopies of defendants exhibits assembled by the Sperry Corporation. All of the documents are arranged chronologically and some have the trial exhibit numbers written on them by hand. None of the records in the Original File was used in this project. The Sperry Corporation deposited the Sperry-Univac Records collection at HML in 1983. Access to the collection was restricted for 25 years from the date of creation, a restriction which expired in 1998.

The University of Pennsylvania’s collection consists of photocopies of depositions, trial testimony, and both plaintiff’s exhibits and the defendants’ exhibits. It appears to be the set of copies retained by the attorneys for the Sperry Corporation. The copies of exhibits were taken after the exhibits were submitted to the Court and after Court staff affixed numerical markers to the first page of each. The Sperry Corporation turned this collection over to the University of Pennsylvania in 1974, primarily for the use of John G. Brainerd, who, in 1945-46, was an associate professor of electrical engineering at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering and the faculty supervisor of the ENIAC project. Brainerd later became Director (or Dean) of the Moore School and served in that position from 1954 to 1970. He retired in 1975, after nearly fifty years on the faculty. The Moore School set aside a storage area in its building for the indefinite retention of this collection, but its existence was not publicized and research in the collection not encouraged. It is unclear what intentions or purposes Brainerd may have had for the collection, but it is known that it languished while it was stored at the Moore School. In 1988, at the age of 83, Brainerd died.

In the spring of 1989 the Office of the Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science (successor to the Moore School and three others) transferred the collection to UARC. Technical services staff arranged and described these papers as the “ENIAC Papers, 1935-1973” collection (Accession number 89.90; collection classification number UPD 8). The run of exhibits at UARC is the largest and most nearly complete collection of ENIAC trial exhibits. The photocopied plaintiff’s exhibits are almost complete, lacking only the IBM exhibits and a small number of exhibits relating to the legal proceeding itself. Some of the IBM exhibits may be found in the HML collection, but none of the exhibits relating to the legal proceedings is contained in either of the other two collections. UARC’s defendants’ exhibits are also principally photocopies of the originals, but do include a substantial number of original exhibits, identified by the markers used by Court staff. UARC’s defendants’ exhibits also include a few original documents, such as the research notebooks of the Eckert-Mauchly computer company.

ARRANGEMENT

As described above, the master collection of ENIAC trial exhibits is composed of two records series, the plaintiff’s exhibits and the defendants’ exhibits. It was necessary, however, in facilitating the creation of the microfilm edition of the collection, to establish two supplemental records series, oversized exhibits and photographic exhibits. The U.S. District Court assigned trial exhibit numbers to all exhibits introduced in the course of the litigation. All four records series follow the Court’s numbering system and are arranged by trial exhibit number. In preparing the plaintiff’s and defendants’ exhibits for filming, the project archivist withdrew all oversized and photographic exhibits and created cross references to them. The oversized and photographic exhibits series are therefore not independent series, but rather subsets of the plaintiff’s and defendants’ exhibits series. The oversize records series contains both plaintiff’s trial exhibits and defendants’ trail exhibits. The photographic records series contains only plaintiff’s photographic trial exhibits.

HISTORICAL NOTE

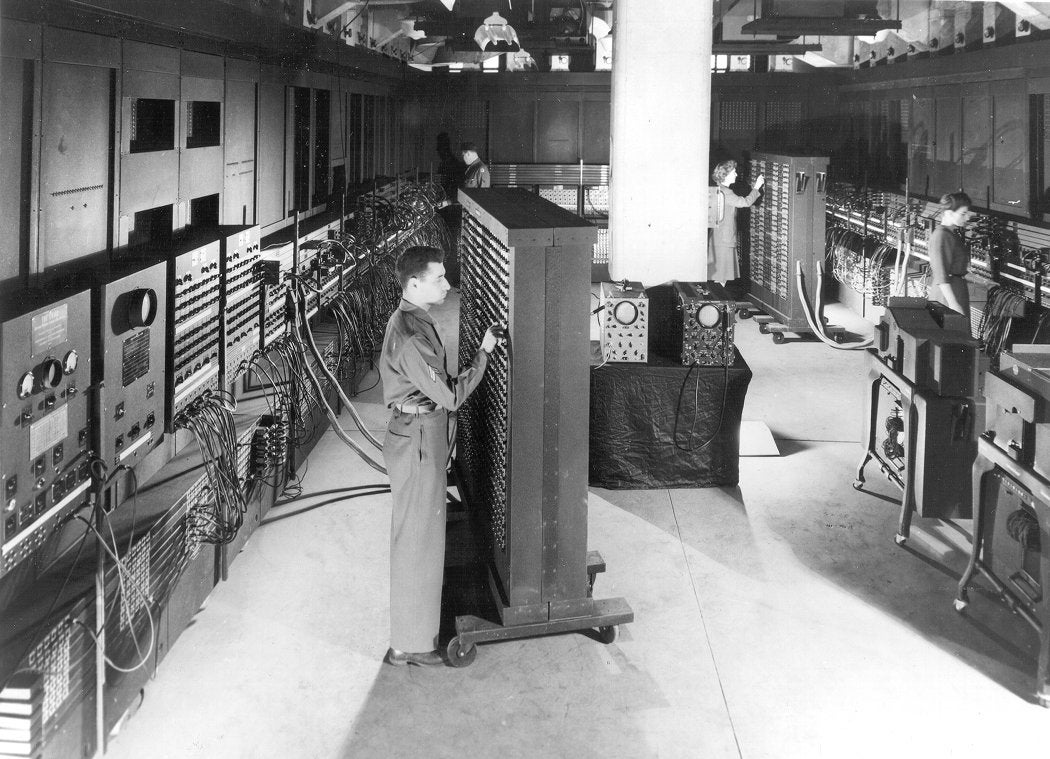

There are two epochs in the history of computing: before the completion of the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (known as the ENIAC), and after. While there are several controversies about the development of the ENIAC and its immediate successors, there is nearly universal agreement on three points: the ENIAC was the watershed project which convinced the world that electronic computing was not merely possible, but practicable; it was a masterpiece of electrical engineering, unprecedented in reliability and computing speed; the two men most responsible for its conceptual and technical success were John Presper Eckert, Jr., and John William Mauchly, both of the Moore School of Electrical Engineering.

The history of computing prior to the ENIAC was long and varied. The desire for a mechanical means of computation was ancient, and had prompted the invention of many devices, from the abacus to the adding machine. These developments culminated in the work of Charles Babbage, whose grandiose, fully mechanical designs had largely been forgotten by the turn of the 20th century, and of Herman Hollerith, whose punched-card tabulators came to the rescue of the 1880 Federal Census. The one feature common to all these early inventions was that the structure was basically mechanical in nature. By the second decade of the twentieth century work was done on finding electro-mechanical computing devices to substitute the slower and inefficient machines. These efforts were undertaken by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology through the initiative of the electrical manufacturers and power companies who needed better equipment to monitor their large and expanding electrical systems. The result of this work was the creation of the differential or Bush analyzer. Though the Bush analyzer was able to perform many mathematical equations, it was still at its core a mechanical device with an electric drive and thus could not produce the greater precision and accuracy desired by scientists. It was partially in response to this slowdown in the advancement of electrical engineering technology that the ENIAC was developed.

The catalyst that advanced electrical engineering and the computer beyond the differential analyzer and to the ENIAC was the demands of the army during the 1930’s and particularly the Second World War. The practical need that the differential analyzer could not solve effectively was the preparation of firing tables-charts that showed how to aim artillery accurately. Too many people and too much time were required to prepare these tables. The federal government was willing to fund research undertaken to improve upon the existing technology. Recognizing this opportunity to expand research and acquire new computing devices, the Moore School of Electrical Engineering of the University of Pennsylvania sought and obtained a contract to develop a differential analyzer of its own. The inadequacies of these mechanical devices at the Moore School were soon recognized by John W. Mauchly, a physics professor, and J. Presper Eckert, Jr., a graduate student.

Eckert and Mauchly believed the best way to improve computer devices was to make these machines primarily electronic rather than mechanical. Despite skepticism from his colleagues in the field, Mauchly thought that vacuum tubes could be used to accelerate calculations and to increase accuracy. Eckert also believed that not only could vacuum tubes be used but also that the existing tubes could be utilized if operated at low voltages. Sometime after Mauchly discussed their ideas with other faculty members and wrote a memo. In 1942 the liaison between the Army Ordnance and the Moore School, Lt. Herman H. Goldstine, heard of Mauchly’s ideals for an electronic computer. Goldstine, who was well acquainted with the shortcomings of the differential analyzer, was greatly interested in this project and suggested that a proposal to the army be written to develop an electronic computer. On April 9th, 1943 the Army granted a contract to the Moore School to build a large general-purpose electronic computer. By end of 1945 the electronic computer developed at the Moore School, known as the ENIAC was operational.

The significance of the ENIAC was soon understood by the many participants in its development who would later vie for recognition and control over the project. The first controversy to arise concerned a paper written in June 1945 by John von Neumann, a mathematician who participated in discussions over the design of the ENIAC. In his paper von Neumann summarized the work of the project without giving any credit to Eckert or Mauchly; thus, presenting to those people in the profession who read the paper that von Neumann was responsible for the project. Patent rights and control over the project were also hotly contested. During an attempt by Irven Travis to restructure the accounting operations and procedures of the Moore School in 1946, Dean Harold Pender wrote a letter to Eckert and Mauchly requiring them to sign a patent release form for all work they have done at the University. He also demanded that they place the interests of the University first rather than their own commercial interests in their work. Because they could not agree to such terms Eckert and Mauchly resigned from the Moore School staff in March of 1946. Though they had left the University and formed their own company, known as the Electronic Control Company, they still encountered problems over the ENIAC.

In 1947 when Eckert and Mauchly began to look into the possibility of taking out a patent on the ENIAC, Army lawyers informed them that the circulation of von Neumann’s paper among people in the profession made the ideas from the ENIAC part of the public domain. Eckert and Mauchly, however, did apply for a patent on the ENIAC in June of 1947. Armed with the potential patent rights to the ENIAC and freed from the constraints of the University, they hoped to succeed in forming a successful computer company; their attempts at this, however, failed when they were unable to maintain a dedicated funding source to cover their expenses. Eventually in February of 1950, Eckert and Mauchly were forced to sell their company, by then known as the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, and the patent rights to the ENIAC to Remington Rand Corporation. Though the ENIAC patent rights were owned by a large corporation, problems over the validity and rights to the invention continued.

While trying to finalize the patent application for the ENIAC, serious problems regarding the patent rights of Eckert and Mauchly, represented by Sperry Rand Corporation, arose in the 1960’s. Sperry Rand was engaged, in the early 1960’s, in litigation with Honeywell, Inc., and other companies, over the infringements of computer patents owned by Sperry Rand. By 1964 Sperry Rand was able to secure a stronger position on their claims to the electronic computer by being granted the ENIAC patent. With the patent in hand Sperry Rand, through its subsidiary Illinois Scientific Developments, Inc., notified all other companies in the electronic data processing field, except IBM, that they were infringing upon the rights the ENIAC patent and must pay royalties. Because of their former difficulties with Sperry Rand in the early 1960’s and anticipated difficulties from a possible suit to collect royalties, Honeywell filed a suit against Sperry Rand in 1967 on the grounds of antitrust violations and unjustified claims to the electronic computer. The case was heard in the 4th Division of the Minnesota District Court (No. 4-67-Civ. 138).

The trial testimony began on 1 June 1971 in Minneapolis before Judge Earl R. Larson with the firm of Dorsey, Marquart, Windhorst, West and the firm of Holladay and Molinar, Allegretti, Newitt and Witcoff both representing Honeywell Inc. The defendants, Sperry Rand Corporation and Illinois Scientific Developments, Inc., were represented by the firm of Dechert, Price and Rhoads. The plaintiff’s counsel presented its case on a number of points that would show the groundlessness of Sperry Rand’s claims to the exclusive patent rights and control of the electronic data processing field. The main points that they presented were generally confined to five areas, viz: a discussion of the work and developments in the field of electronics at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania between 1930 and 1947 as the result of “complex team effort;” a presentation of the state of research in the field of electronic digital computers undertaken at other institutions and companies during the 1930s and early 1940s; a explanation of the attempted domination of the electronic data processing industry by Eckert and Mauchly, and later Sperry Rand Corporation, through numerous patent applications based upon dubious claims, the defects of which were knowingly concealed from the patent office; a demonstration of Sperry Rand’s “pattern of prosecuting patent applications from which they knew no valid patents should issue;” and finally, an exposition of Sperry Rand’s plan to dominate the computer industry through the vigorous assertions of its patents and patent application “portfolio” which it had amassed through cross license agreements with IBM, AT–T, and Western Electric Company, Inc. (both in 1965). The plaintiffs also argued that through its cross-license agreement with IBM in 1956 and settlements with a number of other large computer companies, that Sperry Rand had effectively eliminated any threat of a careful investigation and analysis of the ENIAC patent claims. It was from this position of immense strength, Honeywell contended, that smaller companies would be powerless to fight.

During the course of the trial two major points rose which tested the rights of Eckert and Mauchly to the ENIAC patent and proved fatal to Sperry Rand’s claims. The first point was over where the basic ideals used in the ENIAC’s design originated. Sperry Rand contented that the ENIAC was solely the invention of Eckert and Mauchly; however, Honeywell stated that Eckert and Mauchly had taken the idea from John Vincent Atanasoff and his assistant Clifford E. Berry. Building upon the basic historical view that all inventions are the result of the work of many people over time, Honeywell capitalized upon a visit Mauchly made in 1941 to Atanasoff. During this visit Atanasoff showed Mauchly a small electronic computer he had developed a few years before. Because there were some similarities in the design and operation of Atanasoff’s machine with the ENIAC, Honeywell asserted that Eckert and Mauchly used Atanasoff’s ideas for their own machine. The second major point concerned the filing of the patent in 1947. Because von Neumann had written a paper about the design of the ENIAC and circulated it a year before the patent application was filed, it was argued that the ENIAC had become part of the public domain and could not be patented.

On 10 October 1973 Judge Earl R. Larson presented his final ruling in the case. He determined that the ENIAC patent was invalid mainly because of the two points raised during the trial. He concluded that while Eckert and Mauchly may have created the ENIAC, they did not create the basic ideas used in the assembly of their computer. Judge Larson also believed that the antitrust charge was valid. He stated that the 1956 cross-license agreement between IBM and Sperry Rand was a technological merger and “an unreasonable restraint of trade – an attempt by IBM and S[perry] R[and] to strengthen or solidify their monopoly in the E[lectronic] D[ata] P[rocessing] industry.” Though ruled as an anti-trust violation, the statute of limitations had run out and the charge had to be dropped. Sperry Rand chose not to contest this decision and the findings of the court became final.

SCOPE AND CONTENT

The ENIAC Trial Records Preservation Project is a combined collection of the plaintiff’s and defendants’ trial exhibits presented in the patent case of Honeywell Incorporated vs. Sperry Rand Corporation and Illinois Scientific Developments, Incorporated. The combined master collection that was microfilmed following the original order assigned by the court and the parties to the suit.

The plaintiff’s trial exhibit represents the largest series. There are 27,259 exhibits, each exhibit numbered from 1 through 25686 (material that appears to have been inserted later was given a decimal number). The main portion plaintiff’s series is arranged chronologically beginning with Charles Babbage’s Passages From the Life of a Philosopher, published in 1864, exhibit number one, and ended with correspondence from 1971, exhibit number 21755. This arrangement reflected the chronological argument presented by the plaintiff’s attorneys during the course of the trial. The remainder of the series contains a variety of undated material, supplementary and sometime duplicate documents, photographs, charts and models used during the trial.

As one can readily expect, the plaintiff’s trial exhibit series contains documents that supported the major claims of Honeywell Incorporated in their suit. It contains correspondence, research notes, scientific and publicity articles, schematic drawings, photographs and charts. There is large amount of documentation regarding the research and development of the ENIAC and subsequent computers developed by J. Presper Eckert, Jr., and John W. Mauchly up to around 1951. Most of the material covering period after 1950 relates to the Sperry Rand’s efforts to finalize the patent for the ENIAC and to assert its rights to the major technological claims therein (to support Honeywell’s claims of antitrust actions). Honeywell, as the plaintiff, presented material that demonstrated the state of computer research undetaken by others such as Vannevar Bush and Samuel H. Caldwell at MIT, Vladimir Zworykin and Jan Alesander Rajchman at RCA, and Joseph R. Desch and Robert E. Mumma at National Cash Register Company. Their most important presentation related to the research of John Vincent Atanasoff at Iowa State College and the degree of contact and exchange between Mauchly and Atanasoff. Honeywell also submitted copies of the testimony and depositions of a number of the key figures in the development of the ENIAC and early computers that had be presented in other patent infringement cases.

There are number of large gaps (4,250 exhibits) in the collection that could not be filled with the material from the three participating institutions. Only 940 exhibits from this missing group could be identified from the surviving trial exhibit lists. Many of these exhibits were documents related to the IBM and may have either been removed after the trial or never submitted. It also appears that many of this missing exhibits may have been trial exhibit numbers that were never used but were simply set aside to facilitate the insertion of new material when needed.

The defendants’ trial exhibit series contains 7,167 exhibits, each numbered 1 through 6973, and is about a quarter of the size the plaintiff’s series. Unlike the plaintiff’s trial exhibits, the defendants’ chose to submit material in subject groupings. With Honeywell presenting most of the documents regarding the development of the ENIAC, Sperry Rand’s documents which form the defendants’ trial exhibit series related to specific points that they chose to argue in support of their claims to the patent rights of the ENIAC. Without the attorney’s guide to the organization of this material, it is difficult to determine with certainty the exact limits or descriptions of the subject groupings that form the defendants’ exhibit series. The series does appear to cover many of the same topics present in the plaintiff’s exhibits, as evidenced by the large amount of duplication exhibits. The series begins with copies of the complete United States Patent Office file for the ENIAC patent. There is a heavy concentration of secondary source material, in the form of copies of patents and articles from scientific and technical journals. All contents of this series generally falls within the date span of 1930 to 1965. The series does include correspondence, drawings, research notes, and reports; however, a large portion of the series contains published material such as journal and magazine articles, patents, technical reports and computer manuals. There is much more material in this series that relates to the internal organization, development and research of the Eckert Mauchly Computer Company.

There are also large number (1,042) of missing exhibits which could not be located in the contributing collections. These exhibits appear to fall mostly in the range from exhibits numbered 2566 to 3358. It is possible that some of the missing exhibits were copies of the design and final drawings of the ENIAC. The only missing exhibits that could be identified from original cross-reference sheets in the file were 123 research notebooks. The descriptions provided on the original cross-reference sheets, however, were nothing more than “Original Notebook.” All of the other surviving trial exhibits, which were research notebooks and located near the missing ones indicated that the missing notebooks were probably documenting the research and development undertaken by the Eckert Mauchly Computer Company. In an effort to attempt to locate this valuable material, it was decided to create a new section at the end of the defendants’ trial exhibit series that included the surviving research notebooks from the Eckert and Mauchly Computer Company archives that now form a portion of the Sperry Corporation, Univac Division Records at Hagley. These original notebooks were assigned letters (from A to M) rather than numbers, to distinguish them from the known defendants’ trial exhibit numbers.

Virtually the entire body of documents presented by both parties is composed of photocopies of original documents. The exceptions to this are many of the printed materials, such as patents, articles, books and computer manuals. There were only a few exhibits that were original manuscript material. Part of this latter group include some research notebooks. During the creation of the master collection for microfilming, it was determined that many of copies of the original research notebooks of the ENIAC used as exhibits were poor and illegible. Because the significance of these notebooks not only to the court case but also to the research community, it was decided to substitute for the poor photocopies the original research notebooks from the records of the School of Engineering and Applied Science in the University Archives and Records Center of the University of Pennsylvania. There were also a few other instances in which original material was taken directly from the UARC collections to replace poor photocopies of important documents. Because of the size of this collection, however, the substitution of originals was limited to only the most important documents that could be readily obtained.

The researcher should be well aware of the fact that this entire collection consists mostly of photocopies not original documents. Because many of the copies were poor or deteriorating, the text can be partially or totally illegible in some documents. The original document may still survive it may be difficult to locate if it is still in the hands of the corporation or institution which allowed it to be copied for the trial. The best possible copy of the trial exhibit was chosen from the collections of the three contributing institutions.

Controlled Access Headings

- Corporate Name(s)

- Burroughs Corporation..

- Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation (Philadelphia, Pa.).

- Electronic Control Company..

- General Electric Company..

- Honeywell Inc..

- Illinois Scientific Developments, Inc..

- International Business Machines Corporation..

- Iowa State University..

- Moore School of Electrical Engineering..

- National Cash Register Company..

- Radio Corporation of America..

- Remington Rand, Inc..

- Sperry Rand Corporation..

- U.S. Army Ballistic Research Laboratory..

- United States. Army. Ordnance Department.

- United States. National Bureau of Standards.

- Personal Name(s)

- Atanasoff, John V., (John Vincent)

- Berry, Clifford Edward, 1918-1963

- Brainerd, John G., (John Grist), 1904-1988

- Caldwell, Samuel Hawks,, 1904-

- Desch, Joseph R.

- Eckert, J. Presper, (John Presper), 1919-1995

- Goldstine, Herman H., ((Herman Heine),), 1913-2004.

- Lukoff, Herman.

- Mauchly, John W., (John William), 1907-1980

- Mumma, Robert E.

- Rajchman, Jan A., ((Jan Aleksander),), 1911-

- Von Neumann, John, 1903-1957

- Subject(s)

- Atanasoff-Berry computer.

- BINAC (Computer)

- Computer engineering.

- Computer industry–United States.

- Computers–Law and legislation.

- Computers.

- EDVAC (Computer)

- Electronic digital computers.

- ENIAC (Computer)

- Patent suits.

- Univac computer.

Inventory

|

Guide and Exhibit Index |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

(1) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

(2) |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Plaintiff’s Trial Exhibits |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

1 – 52 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

53 – 146.6 |

1 |

4 |

|

|

147 – 171 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

173 – 266 |

1 |

6 |

|

|

267 – 524.5 |

1 |

7 |

|

|

525 – 616 |

1 |

8 |

|

|

617 – 849 |

1 |

9 |

|

|

850 – 967 |

1 |

10 |

|

|

968 – 980 |

1 |

11 |

|

|

981.1 – 1155 |

1 |

12 |

|

|

1156 – 1303 |

1 |

13 |

|

|

1304 – 1362 |

1 |

14 |

|

|

1363 – 1449 |

1 |

15 |

|

|

1450 – 1584 |

1 |

16 |

|

|

1586 – 1711 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

1712 – 1875 |

1 |

18 |

|

|

1876 – 2093 |

1 |

19 |

|

|

2100 – 2350 |

1 |

20 |

|

|

2351 – 2464 |

1 |

21 |

|

|

2466.1 – 2759 |

1 |

22 |

|

|

2760 – 2887.1 |

1 |

23 |

|

|

2888 – 3275 |

1 |

24 |

|

|

3276 – 3571 |

1 |

25 |

|

|

3572 – 3777 |

1 |

26 |

|

|

3778 – 3871.5 |

1 |

27 |

|

|

3871.7 – 3996 |

1 |

28 |

|

|

3996.1 – 4251 |

1 |

29 |

|

|

4252 – 4457 |

1 |

30 |

|

|

4458 – 4599 |

1 |

31 |

|

|

4600 – 4794 |

1 |

32 |

|

|

4795 – 4976 |

1 |

33 |

|

|

4977 – 5249 |

1 |

34 |

|

|

5250 – 5524 |

1 |

35 |

|

|

5525 – 5733 |

1 |

36 |

|

|

5734 – 5958.5 |

1 |

37 |

|

|

5959 – 6087 |

1 |

38 |

|

|

6088 – 6158 |

1 |

39 |

|

|

6159 – 6237 |

1 |

40 |

|

|

6238 – 6394 |

1 |

41 |

|

|

6395 – 6472 |

2 |

42 |

|

|

6473 – 6691 |

2 |

43 |

|

|

6692 – 6875 |

2 |

44 |

|

|

6876 – 7199 |

2 |

45 |

|

|

7201 – 7385 |

2 |

46 |

|

|

7388 – 7591 |

2 |

47 |

|

|

7592 – 7641 |

2 |

48 |

|

|

7641.5 – 7717.4 |

2 |

49 |

|

|

7718 – 7800 |

2 |

50 |

|

|

7801 – 7988 |

2 |

51 |

|

|

7989 – 8067 |

2 |

52 |

|

|

8068 – 8154.1 |

2 |

53 |

|

|

8154.5 – 8217 |

2 |

54 |

|

|

8218 – 8459 |

2 |

55 |

|

|

8460 – 8575 |

2 |

56 |

|

|

8576 – 8709 |

2 |

57 |

|

|

8709.1 – 8869 |

2 |

58 |

|

|

8870 – 9143 |

2 |

59 |

|

|

9144 – 9351 |

2 |

60 |

|

|

9352 – 9705 |

2 |

61 |

|

|

9706 – 10046 |

2 |

62 |

|

|

10046.1 – 10298 |

2 |

63 |

|

|

10299 – 10598 |

2 |

64 |

|

|

10599 – 10902 |

2 |

65 |

|

|

10903 – 11263 |

2 |

66 |

|

|

11264 – 11585 |

2 |

67 |

|

|

11586 – 11899 |

2 |

68 |

|

|

11900 – 11959.1 |

2 |

69 |

|

|

11960, pt. 1 – 11960, pt. 5 |

2 |

70 |

|

|

11961 – 12166.5 |

2 |

71 |

|

|

12167 – 12541 |

2 |

72 |

|

|

12542 – 12802 |

2 |

73 |

|

|

12803 – 12835 |

2 |

74 |

|

|

12836 – 12971 |

2 |

75 |

|

|

12972 – 13233 |

2 |

76 |

|

|

13234 – 13522 |

2 |

77 |

|

|

13523 – 13654 |

2 |

78 |

|

|

13655 – 13785 |

2 |

79 |

|

|

13786 – 13886 |

2 |

80 |

|

|

13887 – 14264 |

2 |

81 |

|

|

14265 – 14442 |

2 |

82 |

|

|

14443 – 14493 |

2 |

83 |

|

|

14494 – 14599 |

3 |

84 |

|

|

14600 – 14780 |

3 |

85 |

|

|

14781 – 14943 |

3 |

86 |

|

|

14944 – 15111 |

3 |

87 |

|

|

15112 – 15204 |

3 |

88 |

|

|

15205 – 15304 |

3 |

89 |

|

|

15304.5 – 15523 |

3 |

90 |

|

|

15524 – 15823 |

3 |

91 |

|

|

15824 – 15874 |

3 |

92 |

|

|

15875 – 16039 |

3 |

93 |

|

|

16040 – 16161 |

3 |

94 |

|

|

16162 – 16299 |

3 |

95 |

|

|

16300 – 16607 |

3 |

96 |

|

|

16608 – 16733 |

3 |

97 |

|

|

16734 – 16956 |

3 |

98 |

|

|

16957 – 17374 |

3 |

99 |

|

|

17375 – 17798 |

3 |

100 |

|

|

17799 – 18341 |

3 |

101 |

|

|

18342 – 18772 |

3 |

102 |

|

|

18773 – 19182 |

3 |

104 |

|

|

19183 – 19244 |

3 |

105 |

|

|

19245 – 19432 |

3 |

106 |

|

|

19433 – 19717 |

3 |

107 |

|

|

19718 – 19962 |

3 |

108 |

|

|

19963 – 20291 |

3 |

109 |

|

|

20292 – 20508 |

3 |

110 |

|

|

20509 – 20675 |

3 |

111 |

|

|

20676 – 20927 |

3 |

112 |

|

|

20928 – 21006 |

3 |

113 |

|

|

21007 – 21129 |

3 |

114 |

|

|

21130 – 21261 |

3 |

115 |

|

|

21262 – 21285 |

3 |

116 |

|

|

21286 – 21415 |

3 |

117 |

|

|

21416 – 21534 |

3 |

118 |

|

|

21535 – 21611 |

3 |

119 |

|

|

21612 – 21661 |

3 |

120 |

|

|

21662 – 21662.5 |

3 |

121 |

|

|

21663 – 21830 |

3 |

122 |

|

|

21831 – 22446 |

3 |

123 |

|

|

22447 – 22599 |

3 |

124 |

|

|

22600 – 23176 |

3 |

125 |

|

|

23177 – 23566 |

3 |

126 |

|

|

23566 – 23971.3 |

4 |

127 |

|

|

23972 – 24150 |

4 |

128 |

|

|

24151 – 24638 |

4 |

129 |

|

|

24639 – 24927 |

4 |

130 |

|

|

24928 – 25115 |

4 |

131 |

|

|

25116 – 25129 |

4 |

132 |

|

|

25130 – 25335 |

4 |

133 |

|

|

25336 – 25500 |

4 |

134 |

|

|

25501 – 25685 |

4 |

135 |

|

|

Oversize Plaintiff’s Trial Exhibits |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

9 – 2363 |

5 |

201 |

|

|

2368 – 2608 |

5 |

202 |

|

|

2609 – 2861 |

5 |

203 |

|

|

2863 – 3412 |

5 |

204 |

|

|

3413 – 5935 |

5 |

205 |

|

|

5926 – 22299 |

5 |

206 |

|

|

22300 – 25318 |

5 |

207 |

|

|

Photographic Plaintiff’s Trial Exhibits |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

27.1 – 22521 |

5 |

212 |

|

|

Defendants’ Trial Exhibits |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

1 – 2.01-3 |

4 |

136 |

|

|

2.01 – 2.03-4 |

4 |

137 |

|

|

2.03-5 – 2.03-10 |

4 |

138 |

|

|

2.03-11 – 2.03-14 |

4 |

139 |

|

|

2.03-15 – 2.03-18 |

4 |

140 |

|

|

2.03-19 – 2.03-21 |

4 |

141 |

|

|

2.03-22 – 2.03-24 |

4 |

142 |

|

|

2.03-25 – 2.03-31 |

4 |

143 |

|

|

2.03-32 – 5 |

4 |

144 |

|

|

6 – 11 |

4 |

145 |

|

|

12 |

4 |

146 |

|

|

13 |

4 |

147 |

|

|

14 – 15 |

4 |

148 |

|

|

16 – 19 |

4 |

149 |

|

|

20 – 22 |

4 |

150 |

|

|

23 – 32 |

4 |

151 |

|

|

33 – 34 |

4 |

152 |

|

|

35 – 38 |

4 |

153 |

|

|

39 – 41 |

4 |

154 |

|

|

42 – 44 |

4 |

155 |

|

|

45 – 46 |

4 |

156 |

|

|

47 – 616 |

4 |

157 |

|

|

617 – 1099 |

4 |

158 |

|

|

1100 – 1274 |

4 |

159 |

|

|

1275 – 1328 |

4 |

160 |

|

|

1329 – 1451 |

4 |

161 |

|

|

1452 – 1569 |

4 |

162 |

|

|

1570 – 1738 |

4 |

163 |

|

|

1739 – 1917 |

4 |

164 |

|

|

1918 – 1949 |

4 |

165 |

|

|

1950 – 2046 |

4 |

166 |

|

|

2047 – 2146 |

4 |

167 |

|

|

2147 – 2252 |

4 |

168 |

|

|

2253 – 2253.95 |

5 |

169 |

|

|

2254 – 2389 |

5 |

170 |

|

|

2390 – 2549 |

5 |

171 |

|

|

2550 – 3460 |

5 |

172 |

|

|

3461 – 3577 |

5 |

173 |

|

|

3578 – 3844 |

5 |

174 |

|

|

3845 – 4193 |

5 |

175 |

|

|

4194 – 4459 |

5 |

176 |

|

|

4460 – 4589 |

5 |

177 |

|

|

4590 – 4814 |

5 |

178 |

|

|

4815 – 4962 (1) |

5 |

179 |

|

|

4962 (2) – 5005, part 1 |

5 |

180 |

|

|

5005, part 2 – 5100 |

5 |

181 |

|

|

5101 – 5144 |

5 |

182 |

|

|

5145 – 5156 |

5 |

183 |

|

|

5157 – 5248 |

5 |

184 |

|

|

5249 – 5309 |

5 |

185 |

|

|

5310 – 5458 |

5 |

186 |

|

|

5459 – 5563 |

5 |

187 |

|

|

5564 – 5676 |

5 |

188 |

|

|

5677 – 5899 |

5 |

189 |

|

|

5900 – 5984 |

5 |

190 |

|

|

5985 – 6120 |

5 |

191 |

|

|

6121 – 6442 |

5 |

192 |

|

|

6443 – 6650 |

5 |

193 |

|

|

6651 – 6760 |

5 |

194 |

|

|

6761 – 6799 |

5 |

195 |

|

|

6800 – 6830 |

5 |

196 |

|

|

6831, part 1 – part 4 |

5 |

197 |

|

|

6832 |

5 |

198 |

|

|

6833 – 6973 |

5 |

199 |

|

|

A – M |

5 |

200 |

|

|

Oversize Defendants’ Trial Exhibits |

Box |

Folder |

|

|

2.0336 – 2.0341 |

5 |

208 |

|

|

2.0342 – 2.0346 |

5 |

209 |

|

|

2.0347 – 37 |

5 |

210 |

|

|

1100 – 6867 |

5 |

211 |

|