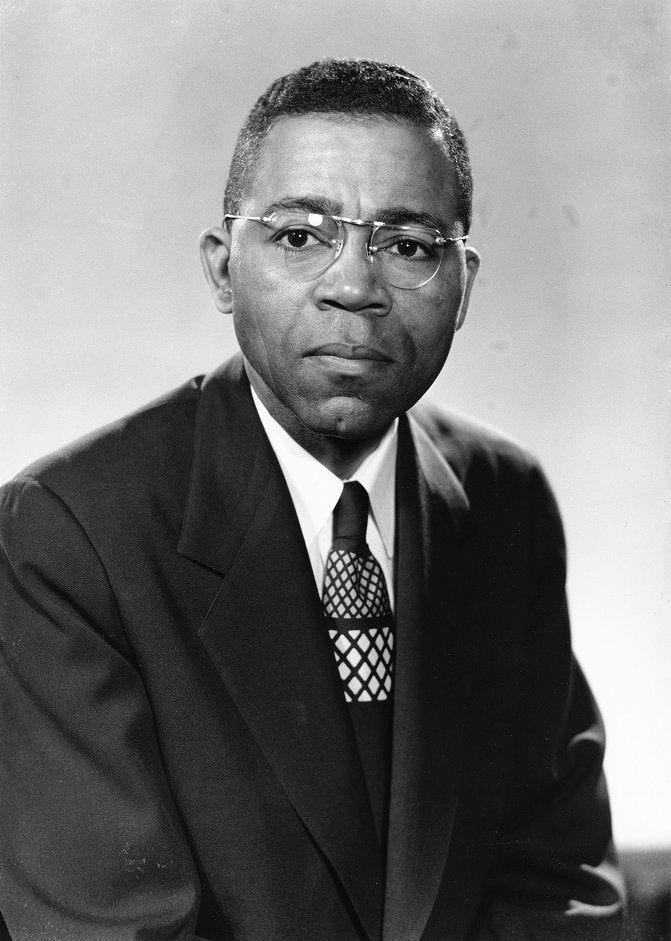

William Fontaine was a native of Chester, Pennsylvania, the second of thirteen children of a steelworker and his wife. His grandmother, an enslaved woman until the end of the Civil War, helped to raise him. His early schooling took place at an all-black elementary school and then at predominantly white Chester High School. As he grew up, young Fontaine witnessed a bloody race riot and the marching of the Ku Klux Klan through Chester. It was not an easy life, but his parents stressed the value of churchgoing and of education, and his widowed Aunt Nettie provided the funds for the children to attend college. He graduated cum laude from Lincoln University in 1930, where he was class president and a member of Omega Psi Phi fraternity. Thurgood Marshall was one of his classmates and Langston Hughes had graduated a year ahead of them.

Fontaine enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania to pursue graduate studies in the field of philosophy, earning a master’s degree in 1932 and the Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1936. During his years as a graduate student he also took courses at Harvard and taught part-time at Lincoln University; one of his students at Lincoln was Kwame Nkrumah, later leader of Ghana. His dissertation was on the “Concept of Fortune in Boethius and Giordana Bruno.” For Fontaine, philosophy was not only an academic discipline, it was the foundation of human society.

After receiving his Ph.D., Fontaine accepted a position at Southern University near Baton Rouge; here he taught philosophy and history, becoming head of the Department of Social Sciences before he left in 1942. During these years, Fontaine was able to do postdoctoral work at Penn and at the University of Chicago during the summers. In 1943, Fontaine worked briefly with his friend Kwame Nkrumah in the Chester shipyards, as part of an effort to challenge segregation in the work force. That same year he enlisted in the Army, serving until 1946 as a sergeant doing vocational counseling. Immediately following service in World War II, Fontaine was called to chair the Department of Philosophy and Psychology at Morgan State College in Baltimore.

Fontaine took a leave of absence from Morgan State for the 1947-1948 academic year to become a visiting lecturer in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. Two years later his appointment as an assistant professor of philosophy earned Fontaine the distinction of becoming the University’s first fully-affiliated African American faculty member. In 1963 he became associate professor, the first black faculty member to receive tenure at Penn.

Fontaine was known not just as a scholar of philosophy, but also as an authority on black culture and the improvement of race relations. Fontaine’s 1967 book, Reflections on Segregation, Desegregation, Power and Morals, published as part of the American Lecture Series, explored the arbitrary use of language such as “White” and “Negro” to control human perceptions and interaction. He was an ardent supporter of civil rights and of racial integration, but was much against the segregation he saw as the outcome of the black power movement of the 1960s. His international travels reflect these interests in black culture and race relations. His time abroad included a 1957 trip to Paris for the Conference on Negro Writers and 1959 trip to Rome for Pope John XVIII’s address to and blessing of black intellectuals promoting black culture. The following year he helped his classmate Nnamdi Azikiwe’s inauguration as the head of the government of Nigeria. In 1962 he represented the American Society of African Culture at a conference in Dakar convened by the President of Senegal.

All these accomplishments are made all the more remarkable by the health problems Fontaine faced. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis during the summer of 1949, just before he began his appointment as assistant professor. During the years that followed as he struggled to cope with the effects of the disease, Fontaine was often forced to take medical leave (three and a half years alone during his first six years as assistant professor). He died in December of 1968, aged fifty-nine. Fontaine was survived by his wife Willabelle Hatton Fontaine and their two daughters, Jeanne and Vivienne.

In 1970, the Fontaine Fellowships were established in honor of Dr. Fontaine.