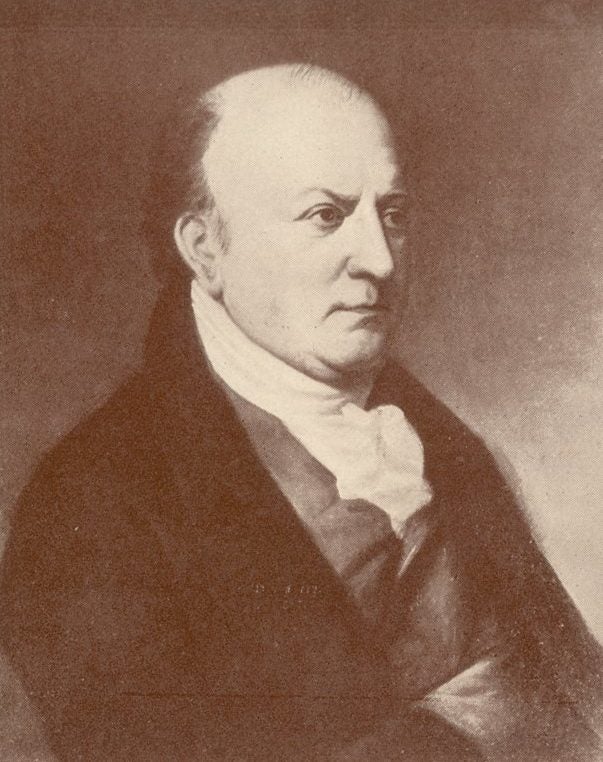

Thomas Cooper was born in London in 1759, the son of a relatively wealthy landowner, Thomas Cooper. He attended University College at Oxford, where he studied classics, but never completed his degree. In 1779 he left the university after refusing to sign the thirty-nine Articles of Faith required for a formal degree. The same year he married Alice Greenwood, with whom he would have five children. One year later, Cooper began attending medical courses in London until the couple moved to Manchester in 1780. There, Cooper pursued his dual interest in medicine and philosophy; he undertook some clinical work and was active in the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

While in Manchester, Cooper joined a firm of calico-printers near Bolton and began to experiment with the industrial production of chlorine as a bleaching agent. From 1790 to 1793, Cooper’s firm grew in size and stature, until a depression in British trade plunged the firm into bankruptcy and ended his experiments with industrial bleaching.

In addition to his burgeoning interest in chemistry, Cooper was intimately involved in contemporary political issues. He became well-known as a lawyer of radical political sentiments, traveling to France during the Revolution as an observer and attracting the oratorical ire of Edmund Burke in the House of Commons. On the tail of a second government warning against seditious speech, Cooper visited the United States in 1793 to prepare a haven for English dissenters.

Cooper and his family soon made their visit to the United States permanent by moving to Northumberland, Pennsylvania, in 1794. They were joined by Joseph Priestly, a theologian and fellow scientist who was a close friend of Cooper, and Priestly’s family. As he had in England and France, Cooper quickly became involved in the new nation’s political life. In a series of newspaper articles later assembled in a volume titled Political Essays (1799), Cooper advocated for freedom of the press and viciously disparaged the Sedition Act. His criticism of President John Adams and the Federalists again attracted governmental wrath, this time from the executive branch. In 1800, Cooper was convicted under the Sedition Act for libeling Adams in a 1799 handbill defending Cooper’s earlier application for a government position. He was subsequently fined and imprisoned for six months, a period in which his wife died. Fifty years later in 1850, Congress remitted the fine.

After the political defeat of the Federalists in Pennsylvania in the first years of the nineteenth century, Cooper was rewarded with a judgeship in northern Pennsylvania. During his tenure as district judge, he settled the infamous Pennamite land dispute between Pennsylvania and Connecticut. By 1811, Cooper had lost the support of radical Republican leaders in Pennsylvania, who removed him from office for “injudicious conduct.” In subsequent writings following his removal, Cooper criticized the political maneuverings of party-ridden governments in both France and Pennsylvania.

After his failed career in law, Cooper turned his attention once again to the field of chemistry. In 1811, he was offered a chair of chemistry at Carlisle (later Dickinson) College. As a professor, Cooper developed new laboratory experiments for his students and also annotated several chemistry texts. He served as a scientific advisor to President James Madison, recommending the study of Congreve rockets and proposing a new type of shell. His analysis of rocket fragments also garnered him commendations from the president.

In 1815, with the college failing financially, Cooper moved to the University of Pennsylvania, where he continued teaching chemistry and mineralogy. His publications during this period were prodigious and contributed substantially to the fields of chemistry, mineralogy, and plant physiology. He became active in a number of professional organizations, including the American Philosophical Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences.

As his books grew in prominence and relevance to the slowly emerging field of scientific medicine, Cooper applied for the chair of chemistry in the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania. Although he did not receive the position, Cooper continued to advocate for the close connection between chemistry and medicine.

In 1819, Cooper left the University of Pennsylvania for Jefferson’s new college in Charlottesville, Virginia, where he was officially elected professor of chemistry, mineralogy, natural philosophy, and law but never taught. With the opening of the college postponed, Cooper began to teach chemistry at South Carolina College in Columbia. In 1820, he was also appointed professor of geology and mineralogy and was elected president of the college. He continued to work to advance the burgeoning field of scientific medicine, pressing for the formation of a medical school in the South.

Cooper was extremely popular among many of South Carolina’s and the nation’s leading political figures up until his death. He wrote extensively on such charged issues as states’ rights and slavery, and despite his earlier opposition to the slave trade, he owned enslaved people and espoused the biological inferiority of blacks. In a speech delivered in 1827, he quite presciently predicted the demise of the Union.

Cooper remained an active figure at South Carolina College in the last years of his life. He battled encroachments of religion in education and successfully defended himself before the Board of Trustees against allegations from the clergy. After he resigned his position in 1833, the governor of South Carolina appointed him to compile and edit the statute laws of South Carolina. Cooper died in 1841 and was buried in Trinity Churchyard in Columbia. The library of the University of South Carolina still bears his name.